Giselle Beiguelman

Warning: Sensitive images

I apologize for the harmful feelings thee plants’ names (scientific and popular) presented in this essay may cause to some groups.

These are common names in specialized literature, gardening stores, and websites and do not reflect the artist’s opinion.

Prologue: The garden with no species

The world’s most famous garden, the Garden of Eden, perhaps never existed. And if it did, it certainly wasn’t as in the traumatic story that marks Judeo-Christian cosmogony with the expulsion from paradise. Whether fact or fiction, what is important to remember is not the famous narrative of the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge that enchanted Eve (hooray for her!), but that its center was occupied by a strange tree—the Tree of Life—whose species is not specified in the Bible.

Scientists, philosophers and religious scholars have debated in their writings whether it was a ghaf (Prosopis cineraria) or a date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) and have taken inventory of how many species are cited in the Old and New Testaments. A pretty difficult undertaking, given that according to traditional knowledge a plant is not a thing in and of itself, and its names refer to its uses, groups, moments and contexts.

What prevails in the sacred scriptures, at least concerning to plants, is the kaleidoscopic logic that Levi-Strauss identified among the indigenous peoples, which presupposes models of provisional intelligibility.

The two species that science has identified as the ghaf and the date palm are quite distinct, but have one thing in common: both survive in the most adverse conditions, such as lack of water and in sandy soils.

The ghaf has an impressive ability to remain green and leafy despite the inhospitable arid climate it inhabits. The best-known ghaf is over 400 years old. The tree, which is 9 meters tall, is planted in the Bahrain desert, where the mythical Eden is speculated to have been located, and receives tens of thousands of tourists annually.

In Jewish mythology, the date palm symbolizes beauty, prosperity, and regeneration, which turns bitter into sweet. This, say the Kabbalists, is inscribed in its original Hebrew name, formed by the words tam (complete, finalized) and mar (bitter). The interpretation also alludes to the resilience of Tamar, a biblical character who was widowed twice by the sons of the same man and, for this reason, was sent back to the house of her father. After being deceived by Judah, her father-in-law, who did not marry her to his third son when he came of age, she disguised herself as a prostitute, became pregnant and married him, freeing herself of the stigma of being cursed. A blow to the chauvinists in the Book of Genesis.

In Muslim culture, the date palm is a symbol of prosperity and hospitality, and also has religious connotations, in addition to medicinal uses. The Ramadan fast is broken with three tamars (dates), and the fruit is mentioned 23 times in the Koran. It is customary in some countries to eat dates before breakfast, and some say that one date provides enough energy for a Bedouin to walk for three days.

The date comes from a palm tree that can take as long as 80 years before it bears fruit. A well-known Arab proverb says: “He who plants date palms, will not harvest dates”. The ancient proverb describes a generous ecological act, conscious of the fact that this planting and cultivation does not affect the present, but rather the future of those who follow us. It is interesting to note that similar reasoning is present in the Jewish law that says one “Shall not destroy”, which prohibits the cutting down of fruit trees.

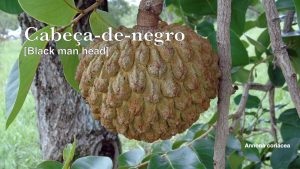

There is debate whether the word comes from Arabic or Hebrew. Both languages have the same name with few differences in pronunciation, and both can be translated as palm tree. Their meanings, however, transcend their direct relation to the plant. In Portuguese and in Spanish the fruit name is “tâmara”. If there is something to commemorate from the Iberian colonization, it is not calling its fruit a date, a derivation of its scientific name (Phoenix dactylifera, Phoenician finger), as in English and French. The analogy between plants and humans is one of the colonial anachronisms that anthropomorphizes the plant world, via taxonomy, making plants a reflection of man.

Act I: Laboratory of prejudices

Throughout the 18 th century, botany became institutionalized as a technology of power that used taxonomy as its instrumental knowledge. Dissected, compartmentalized and lined up in a row in European botanical gardens, the world of plants is converted by colonial empires into a seemingly neutral space, while in fact inside it the patriarchal, racial and religious prejudices are projected.

What follows the cataloging of the world is the collection of species that will feed the plantations. It was no coincidence that the Boundary Demarcation Commission, which defined the borders between the domains of Spain and Portugal, in 1751, was accompanied by the Orinoco Expedition. This scientific expedition was led by the Swede Pehr Löfling (1729-1756), the beloved disciple of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the father of taxonomy, to whom he dedicated his work on Hispanic America. In recognition of his deeds, his master named a botanical genus after him as a tribute: Loeflingia. This was not uncommon, but rather a dynamic of the colonial extractivist past.

Colonialism expropriated not only land, but also plants from their relationship to the environment and the society to which they belonged. Their environment and their medicinal and religious uses are submitted to a symbolic ritual of erasure through the introduction of new scientific names given to things.

The word “botany” appeared for the first time in 1682, in the work of the English naturalist John Ray (Methodus plantarum nova). He tested a classification method for plants based on habitat, on their uses and the similarities between their primary parts (leaves, stems, roots, etc.). The method would have undermined the vast herbalist tradition and its religious motivations for recreating the Garden of Eden, which marked the medicinal gardens that peaked in popularity during the Renaissance.

However, this method would breathe new life into aspirations of formulating a universal understanding of nature, which were commonplace in modern science. But these aspirations would only be fully attained almost a century later. A classification system of this scope required a uniform system of nomenclature, as the one created by the Swedish botanist Linnaeus, in his work Species Plantarum, in 1753.

If the classification system created by Ray marked a separation between botany and medicine, the system created by Linnaeus cast plants out from the totality of life. In the binomial system created by Linnaeus, plants receive a first and a last name in the language of the European cultural elites, Latin. The plant world incorporates the identities of kings, noblemen, popes and renowned scientists, accompanied by pompous words that allude to the geometry of the shapes of their leaves, trunks and roots, using human characteristics such as ears and vaginas.

Throughout the colonization of the Americas and the African continent, the principles of progressive evolution and natural selection contaminated everything from the economy to the imagination. This prejudice gained laboratory ballast and rooted itself in the collective imagination.

Act II: Nomenclature is a ritual of erasure and oppression

Naming something scientifically is to take possession of it, denying the material and symbolic possession of nature to original peoples. In the scientific organization of the world, the Jatobá (West Indian locust), for example, is no longer the tree of hard fruits, sacred to original peoples for its curative powers, but rather a Hymenaea courbaril, in the taxonomy of Linnaeus, in reference to the female hymen, due to the rigidity of the peel of its fruits.

Hymenaea or Hymen, in Greek mythology, is Hymenaeus, the god of marriage. Represented by a youth who carries a torch and a veil, he is the one who unites, who binds the two parts. Although no direct reference is made to the vaginal membrane which tears during sexual intercourse, the term assumes this connotation in the medical literature of the 16th century, directly associating virginity, marriage, and the supposed functions of women in society (procreating and serving, primarily).

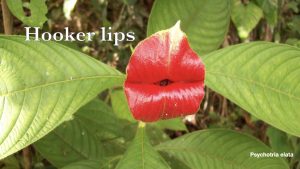

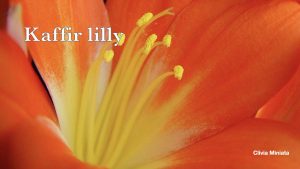

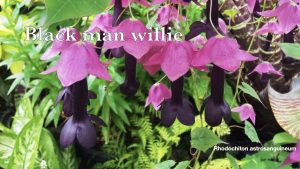

There are many plants with names that cast women in a chauvinist approach, such as Shameless Mary (Impatiens walleriana), Hooker lips (Psychotria elata), and Nipllefruit (Solanum mammosum). But this also occurs in the scientific nomenclature, in which there are many plants with scientific names that allude to Greek nymphs—beautiful demi-goddesses who never grow old and favor men and nature—who gave their name to the genus of Nymphaeae, which enchanted the painter Monet.

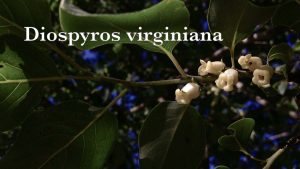

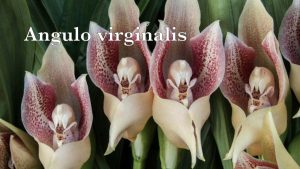

More common are flowers, generally white ones, which are named as virginiana, virginica or virginicum, among others, making direct reference to female virginity and its association with purity and delicateness. Places uninhabited by Europeans, which appeared in various old maps as terra incognita, are commonly known as “virgin territory”, a world to be subjugated and opened up to devastation. There is no denying it: colonialism really does rhyme perfectly with patriarchalism.

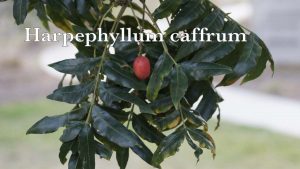

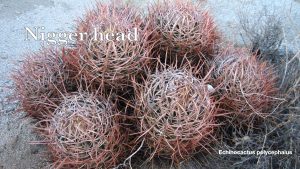

Blacks are the target of different types of prejudice, expressed in common names, but also in scientific names. The names of plants that contain kaffir or cafrum are highly offensive. A term derived from Arabic for “non-believer”, cafir became, among the European colonizers, a generic synonym for negro, and then cafre, rude, in Portuguese, which became a synonim for slave.

For these reasons, today, cafir is considered, in South Africa, as an equivalent to the repudiated N-word.

Other derogatory names contain the word Hottentot. This was how the Dutch generalized all the non-Bantu peoples of South Africa. The word was synonymous with cannibal, savage, and also alluded to some physical stereotypes, such as protruding lips and buttocks, as is evident in the degrading iconography associated with Hottentot Venus, a princess that was taken to Europe, where she was humiliated in supposedly scientific expositions for the entertainment of white elites.

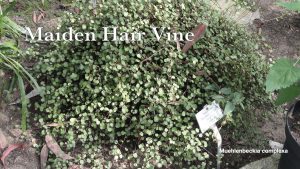

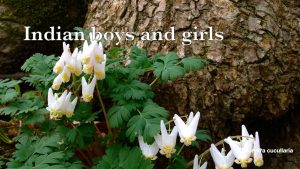

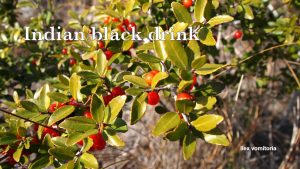

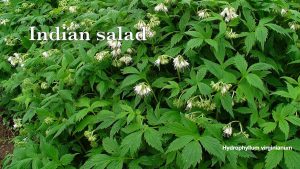

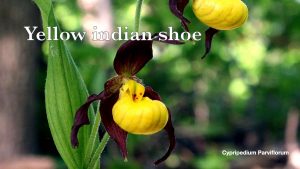

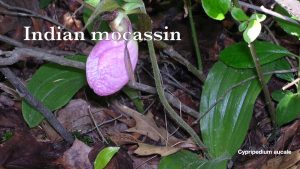

Prejudiced names are also revealed in the projections of white European culture on the shapes of plants, conjugated into terms offensive to original peoples, who are described as “indians”. This is what Christopher Columbus, who believed he had landed in the Indies, called the native inhabitants of the Americas. Indians. Over 350 plants in the English language are known as “Indian” and some elements of white culture, such as Indian moccasin and Indian hemp.

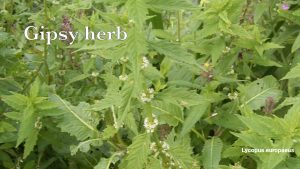

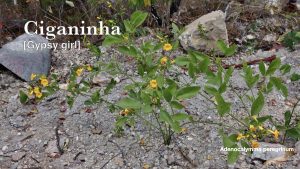

Invasive plants are called Gypsy weeds. The adjective is problematic not only because it generalizes peoples with different histories, but especially because it appears in dictionaries as synonymous with an unlicensed business and offensive meanings. The ethnic groups are Roma, Sinti and Kale.

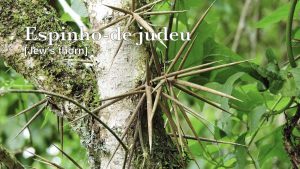

In the case of the Jews, anti-Semitism focuses on physical traits, such as stereotypically large ears, and cultural traits, such as the beards of the orthodox. It also conforms to ancient myths, such as the one about the people who killed Jesus, which appears in the reference to the crown of thorns worn by Jesus Christ, present in various plants. Some examples are Auricula judae (Jew’s ear, Judas’s ear, in various languages), Judenbart (Jew’s beard, a species of begonia that produces small white flowers) and the common Christ thorn (Euphorbia milii, which in Brazil also has a misogynist version, colchão-de-noiva [Bridal bed]).

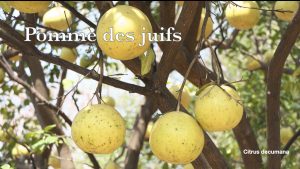

As occurs with indigenous peoples, various plants present in Jewish rituals and herbalism have been classified as “Jewish”. Judenöpfel (Pomme des juifs, Cedro all’ Ebrea) is a common name for the pomelo (Citrus decumana). In Hebrew it is called the etrog, a plant directly associated with the customs of the Jewish festival of Sukkot (Feast of Booths), which involves four plants in its rituals (lulav, a date frond, hadass, the leaf of a myrtle tree, arava, the branch of a willow tree, and etrog, the most sacred, since it is heralded for its taste and fragrance). Also known as “Apple of paradise” in German (Paradiesapfel), it can be found in medical books in this language since the 16 th century.

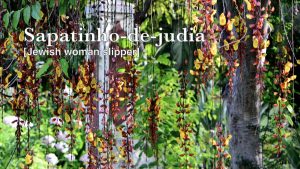

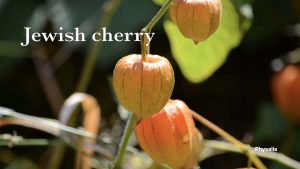

Other “Jewish” plants are the Corchorus olitorius (Jew’s mallow), and eggplant (Jew’s apple), two plants common in Middle Eastern cuisine, and Judenkirsche (Jewish cherry, Physalis), known as the groundcherry in English. Despite the apparent innocent association, the name is completely anti-Semitic. The small fruit is wrapped in a leaf that alludes to the infamous hat that Jews were forced to wear in medieval Europe (Judenhut, Coiffe juive, Pilleus cornutus), as an imposition of the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) so they could be identified and distinguished from Christians.

We must not overlook Der Giftpilz (The poisonous mushroom, 1938), an illustrated children’s book that was central to Nazi pedagogy. Divided into 17 chapters, the book taught, through captioned caricatures and drawings, that one cannot trust Jews. “Just as it is often hard to tell a toadstool from an edible mushroom, so too it is often very hard to recognize the Jew as a swindler and criminal… They disguise themselves, try to be friendly, stating their good intentions to us a thousand times. But you should not believe them. Jews they are and Jews they will always be. For our people, they are poisonous.”

This vision of the Jew as untrustworthy, who pretends to be something he is not, is repeated in other common names of plants that are assigned the word Jude (Jew in German). Among the mushrooms alone there are six species called Judenpilz (Jewish mushrooms), which received this name either because they are poisonous or because they are considered inferior to other types.

There is the Spanish chestnut (Castanea sativa) and there is the Judenkest (Jewish chestnut, Aesculus hippocastaneum), which was fed only to animals. And there is also Juudenspeck (Jewish bacon) for the Butomus umbellatus (a species of flowering rush, whose rhizomatic roots are edible), Judenfleisch (Jewish meat), Judenschinken (Jewish ham) and again Jewish bacon for the Capsella bursa-pastoris (Shepard’s purse, an herb whose pods are edible). There is no ethno-botanical basis that justifies its association with Jews. What prevails here is the supposed inferiority in relation to foods that are considered superior.

It is not surprising that some “Jewish” plants have, in German, other common names that characterize them as dog-like, savage or gypsy-like. This is the case of the Allium ursinum (Wild garlic), which is known as Judenzwifel (Jewish garlic) and also as Bärenlauch (Bear leek) and Zigeunerknoblauch (Gypsy leek). These groups (Jews and gypsies) also share an association with filth, which is evident in plants such as the greater burdock (Arctium lappa) and the Bidens tripartita, known as Juddeleis (Jewish lice) and Zigunelai (Gypsy lice). In both cases, these are plants in which the inflorescence resembles the long beards characteristic of the two peoples.

The movement for taxonomic renaming has mobilized a number of scientists, though little progress has been made. In 2006, Sweden decreed the renaming of the Judenkirsche and all those that had anti-Semitic connotations, which was not well received by some discussion forums on the Internet. One person reacted to the overhaul:

I like Physalis alkengi, Juutalaiskirsikka in Finnish and Judenkirsche in German, in other words, “Jew’s cherry”, since as soon as they escape my garden, I can say: Wir müssen die Judenkirschen ausrotten! (We must eradicate the Jew cherries!).

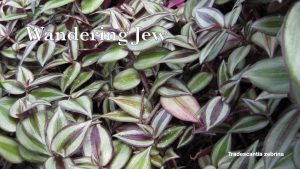

Explicitly, as in the commentary above, or naturalized by daily use, anti-Semitic terminology shows its cultural force and ability to spread. Something that is evident in the linking of the Jew with deicide and betrayal, clear in the still quite common ritual of the burning of Judas, which also lends its name to Cercis siliquastrum as Jüdischer Baum, Jewish tree in German, and Juda’s tree, in English and French. Nothing, however, approaches the scope of dissemination and virulence of the maligned legend of the Wandering Jew, which dominates the plant family Tradescantia in various languages.

The legend has circulated in Europe since the 13th century. It tells the story of a man, Ahasuerus, who upon seeing Jesus walking to the Calvary, called out: “Crucify him!” In response, Jesus cursed him to walk the earth tirelessly, waiting for his return until the end of days.

Although Catholic church scholars maintain that this man was the Roman Cartaphilus, one of palace guards of Pontius Pilate, the legend of the Wandering Jew endures as part of the oral tradition of Good Friday. It was published in Germany in the 17th century and popularized by the version by Eugene Sue, in the mid-19th century, and by the etchings of Gustave Doré.

The legend of the Wandering Jew was also used in works of art against anti-Semitism, as in the film The Wandering Jew (1933), starring Conrad Veidt, the unforgettable sleepwalking assassin of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920), and in paintings by Marc Chagall (1887-1985). But undoubtedly the version that prevails up to this day is that of Nazi Germany, in the form of the propaganda film Der ewige jude (The Eternal Jew, 1940): the parasitic, millionaire Jew conspiring internationally to dominate the world.

Act III: “Humanity is a garden…”

The basis of the Nazi extermination policy was eugenics, a type of scientific racism whose origins lie in the taxonomy of botany of the 18th century. It was Linnaeus who first divided men into:

- Europeanus (whites): light, wise, inventors

- Asiaticus (yellows): stern, haughty, greedy

- Americanus (reds): unyielding, cheerful, and free behavior

- Africanus (blacks): sly, sluggish, neglectful

This model gradually became more sophisticated in the following decades, marked by the study of different craniums by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, the father of anthropology, and the principle of natural selection by Darwin, which particularly impacted his cousin, Francis Galton, creator of eugenics, for which this specialty is named.

The works of the American physician Samuel Morton, published in 1839, and of the French writer Arthur de Gobineau, in 1835, established them as pillars of scientific racism, which fed Nazi Aryanism and are still present in white supremacist discourse today.

It is in this context that the enslavement of blacks and indigenous peoples gain scientific legitimacy and the racialization of Jews is first attempted.

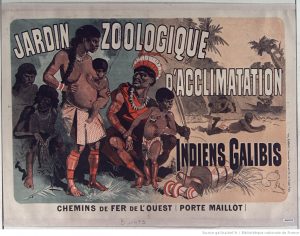

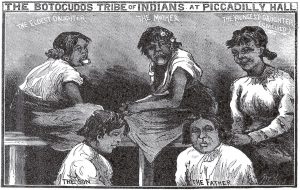

Like plants and animals, human bodies are objectified, dissected and oftentimes instrumentalized as entertainment for the masses. It is impossible to forget here the exposure of the group of Botocudo Amerindians, taken from their native land, in Espírito Santo, to Rio de Janeiro—where they were presented at the Brazilian Anthropological Exhibition (1882) organized by the National Museum, in which representatives of other indigenous peoples were also exhibited—and from there onward to Europe.

The case of the “Botocudos of Brazil”, as we know, was not exceptional. In Europe, the exhibition of indigenous peoples and blacks from afar was common in zoos, in animated “scientific” meetings and in spectacles of “entertainment”. We need only to remember the award-winning film Vénus noire (2010) by Abdellatif Kechiche, which tells the story of the Hottentot Princess, to conclude: colonial violence cannot be put into words…

And it is within the scope of colonialism that eugenics emerges. Francis Galton coined the term eugenics in 1883, in the book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. His motivation was to offset the “slowness” of the processes of natural selection that Darwin said would exterminate the savage races. But this would take centuries, and Galton dedicated himself to creating mechanisms to improve the human species, changing the composition of populations and favoring the reproduction of certain types to the detriment of others.

Proposed as a science, eugenics soon became a social movement. In the United States, its popularity started in 1907, with the approval of laws on sterilization and the prohibition of interracial marriages. Another country on the vanguard in this field was Brazil, whose Eugenics Society dates back to the 1920s. Headed by the physician Renato Kehl, its members included the poet Jorge de Lima, the educator Fernando de Azevedo and other loyal followers, such as the writer Monteiro Lobato.

In Nazi Germany, eugenics became the official policy of the state starting in 1933. The results of this delirium are reflected in the terrifying number of deaths: 6 million Jews, 250,000 Sinti, an unknown number of blacks (but certainly in the hundreds of thousands), at least 200,000 mentally ill and many thousands of homosexuals, communists and political opponents, classified as antisocial.

For the eugenicists, humanity was a garden that, in order to flourish, must rid itself of weeds. These ideas can be read in an edition of their writings, organized by their most important disciple, Karl Pearson. “Weed”, however, does not refer to any plant of any species or genus or any category recognized by current scientific taxonomy.

“Weed” is just a name for any plant that grows where humans don’t want it. Its classification as mala hierba is another vestige of colonialism. They are plants that do not serve the extractivist economy. They are plants that survive in adverse conditions. They are plants that cannot be easily exterminated. They are plants that not even radical eugenics can control.

Act IV: Taxonomy is a technology of power

The relationship between colonialism and appropriation is endemic. The domination of nature and the subjugation of non-male, non-white bodies are strategic to its success. The long colonial enterprise called on scientists not only to make maritime expansion possible, but also to legitimize the annexation and control of territories.

This belief in science is used to compensate mankind’s insignificance before nature and to subjugate its diversity. Forms of ancestral knowledge are neutralized by the ritual of erasure of scientific nomenclature. Anthropological and ethno-botanical studies have shown that the practice leads, on the one hand, to the contraction of the imagination and, on the other, to a substantial loss of knowledge, in anything from medicine to chemistry.

“[Modern] Science and empire are cause and effect of one another”, said La Fuente and Valverde. On the one hand, the colonial empires demanded that scientists and their patrons share the belief that things of nature can be captured in words and diagrams. On the other, traveling naturalists believed that natural processes could be drawn, recorded in scientific articles and cataloged.

As a general science of order, taxonomy is a formula for tabulating the world, used to organize it based on its similarities and differences. From the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew to the American database JSTOR, which connects herbariums from around the world on the Internet, the prevailing logic is one of coordinated centralization of information, geopolitical preeminence and normalizing power.

Studies on Afro-diasporic and indigenous ethno-botany show that the subjugated, despite their extreme oppression, have always subverted the order of nature fabricated by colonialism. From the enslaved who concealed grains of rice in their hair to ensure the continuity of their food customs with their children, to their insistence on indigenous names in our flora, the entire history of resistance is told. More than just a history, it is the formulation of another ecology.

Recent research has shown that the colonial empires did in fact expropriate and normalize flora everywhere they moored their ships and caravels. It is also true that this domination was corrupted by cultural infiltration whereby the subjugated cultures stamped their semblance and tastes on the new landscape. Dendê (Agrican palm oil) and quiabo (okra) are not just words of African origin but transplanted traditions that inhabit anything from Yoruba rituals to Brazilian cuisine. Here, we must recognize the permanence of indigenous names in popular terminology. Babaçus, jacarandás and ipês attest to the strength of resistance to the memoricide of the cultures of original peoples.

This memoricide begins with the renaming of the tree Pau-Brasil (Brazilwood) that gave the country its name, Brazil. Ibirapitanga (red tree), as the Amerindians called it, was the first product commercialized by the Portuguese. Classified as Caesalpinia echinata, it was renamed Paubrasilia echinata in 2016. The idea was to ensure that it had its own “genus” in taxonomy. In this way, scientists of the 21th century corroborated the thesis of national pride, denying, once again, the right of indigenous peoples to their memory.

There is nothing natural about the classification by Linnaeus, which follows two basic guidelines: hierarchy, which submits plants to a Kingdom (in this case, the plant kingdom) and divides them into classes, orders, genera and species; and an organization that places plants in these categories, according to their reproductive characteristics (the number of stamens and pistils). Sexist and binary, the taxonomy by Linnaeus assigns superiority to the presence of supposedly male organs (stamens) over plants in which pistils are dominant. This leads us to believe that masculine authority must be an atavistic given of nature, while reinforcing societal prejudices of the time, which are valid even today.

An important element of the tactics of erasure of cultural plurality is the misogyny that dominates botanical classifications, largely formulated by white men. This perspective also contributed to corroborating the binary perspective that underpins the patriarchal culture, in which a woman is inferior and gender diversity is restricted to males and females.

Paradoxically, however, the plants considered most complex in the theory of evolution, the angiosperms, are mostly hermaphrodites. These are the ones that produce flowers and fruits and, despite their name being linked to the male gender (angio, from the Greek for “vessel” + sperma, “seed”), they have the male and female reproductive organs (androecium and gynoecium).

An entire line of feminist investigation and queer studies is devoted to calling attention to the forms of concealment of these dynamics throughout history. At the same time, these works divest the prejudiced associations between gays and floral symbolism, giving them new connotations and positiveness. Among these terms are Pansy flower, a synonym of sissy, and the violet, known as the Sapphic flower, or the flower of Safo, an author of Lesbian erotic poetry from the 7th and 6th century BC, who inhabited the island of Lesbos.

Other important flowers among LGBTQIA+ symbols are the green carnation of the writer Oscar Wilde, and the lavender, whose purple coloring is one of the ways of identifying LGBTQIA+ movements, but which has also been used to exacerbate discrimination since the 1920s. The high point of this anti-gay crusade was operation Lavender Scare, in the 1950s in the United States government, which targeted homosexuals in civil service and led to the mass dismissal of over 5,000 people. In a historic turnaround, in 1969, crowds carried lavender branches in New York, in one of the most important marches of the period to affirm the rights of homosexuals, transforming the lavender branch into a symbol of empowerment of these groups.

It was in this direction, in an appropriation of derision and offense in order to transform it into an agenda for liberation, that I accepted the assignment of “wandering” to Jews as a sign of force and resilience. In line with some presumptions of contemporary philosophy, I used wandering as a derivation of nomad, which for Deleuze and Guattari is the social condition that performs the capacity for change, the deterritorialized body that flows, escapes from the processes of domination.

Act V: Every weed is a rebellious being

For about a year and a half, I have been researching plants with racist (demeaning to blacks, indigenous people, Roma, Sinti and Kale), misogynistic and anti-Semitic names. I collect everything, scientific and common names. There are thousands of species. Actually, one can say that all nomenclature is offensive due to the erasure that it produces in the culture of original peoples. All nomenclature is offensive due to the way it enshrines the dominator, by associating the names of kings and queens with their scientific terminologies.

The research process began when I was presented with a “Wandering Jew” in a brilliant artistic occupation by C. L. Salvaro, who used an abandoned house with climbing plants, on which I wrote a review at the request of Central Galeria (São Paulo). At that moment, I was chilled. This name is a traumatic trigger for any Jew due to the anti-Semitic power it possesses.

Astonished, I remember arriving at home and searching for it on the Internet. I could not believe it was true that a plant could have this name. But it was. A Google search returned books on the wandering Jew and ads, in various languages, for this plant that I like so much, in addition to associating it with a series of historical figures persecuted by different circumstances, such as President Dilma Rousseff, at the time of the proceedings that culminated in her impeachment.

Disconcerted, I began to research the relationships between botanical taxonomy and prejudice. To my great surprise, I discovered that most of these plants, which have pejorative and derogatory names, are considered weeds! And they are beautiful.

This demeaning term (weed) in the hegemonic thinking became a symbol of resistance for me. As in the samba of Zé Kéti, immortalized by the voice of Elza Soares, they seemed to be saying: “They can arrest me, they can beat me, they can even starve me … If there is no water, I dig a well”.

Weeds are just like this. They climb rocks, they fit in between trees. They reemerge. They resist. Like the enslaved, who trafficked the Imperial palms—a symbol of power for the monarchy and of Brazilian plantation wealth—by swallowing the seeds and storing them in their feces as contraband. Like the Jews, who have endured every cycle of persecution, from the crusades to the Inquisition and Nazism, and managed to stay alive. Like the indigenous peoples and their ancestral knowledge, having endured five centuries as the victims of policies of erasure and genocide. Like the Roma, Sinti and Kale peoples, known as gypsies, despite all of the dictionaries that associate them with deception and jest. Like women, erased from all the histories and violated in every sense.

Undesirable, indomitable, cursed, weeds are the perfect metaphor for the fight for the right to life. Rebels, they challenge a world dominated by a natural order that does not exist, geared to producing goods.

Despite the abominable results during World War II, eugenic societies endured until the mid-1960s, leaving profound marks on contemporary culture. And this is not simply a matter of beauty contests and Johnson’s babies. In cutting-edge knowledge, in everything from classical botany to artificial intelligence to gene editing, the keyword of eugenics is standardization.

People, plants and animals are submitted algorithms designed for life or products and the same technological principles employed industrially: design, quality control and predictability.

In the field of image technologies, these principles are present in surveillance systems. But they are also applied to photography and audiovisual production, to create figures that are more real than real, enabling the substitution of humans by models or actors that do not exist, making politicians say things they never said, or creating revisionist discourses that deny anything from the Holocaust to the lunar landing.

These are called deepfakes, and they are made using artificial intelligence that creates new data based on other data, identifying and combining internal patterns while downplaying dissonance.

The process of generative imaging, created with artificial intelligence, is shockingly similar to that which Francis Galton used in his study of eugenics, for which he created a photographic method: the composite portraiture. In this process, Galton superimposed different photos and erased their differences, to identify the generic criminal or the generic Jew.

The composite portrait, wrote Galton in 1879, “is one that represents no man in particular, but portrays an imaginary figure possessing the average features of any given group of men”. This is basically what a Generative Neural Network does: it recognizes patterns, in detriment to particularities.

But what about things that fall outside the pattern? What place will they occupy in society?

Epilogue: Weeding the world is necessary

We know that vision is a biological attribute, but seeing is a cultural construction. Western culture’s difficulty in understanding the world outside the parameters of Renaissance frames and windows is undeniable. Paintings and books prove it. Based on this reasoning, I ask: will there come a time when the computational view becomes so hegemonic that we can no longer see what falls outside of the pattern, in the same way that we find it difficult to understand what falls outside the rectangular canon or the frame of a painting or page? Are we on the cusp of an era of machine eugenics?

This is when I decided to dedicate myself to a kind of “engineering of a reverse philosophy”. By combining images that purposely break the production chain of more real than real images, feeding the system with incongruent data, like plants of different species, but always with names demeaning to Jews, blacks, women, indigenous peoples and peoples known as “gypsies”, by forcing the system to operate its synthesis and, in this way, generate an image that has no intention of tracing the real, but rather operating outside of nature.

This procedure gave rise to the series Flora rebellis, a set of five video recordings of the displacement of artificial intelligence by thousands and millions of pieces of data that compose a model (in my case, “Jews”, “blacks”, “women” etc.), in a search for coinciding patterns in the layers of the archives of images that compose them.

This space, in which data revolve inside a model, is called a latent space, since it is not observable by the human eye. We are capable, for example, of recognizing that a photo portrays a plant and not a person, but we are not capable of observing the countless layers of information of a digital image, which include anything from internal coordinates to the type of camera used.

The video recording, therefore, shows the different paths that machine processing could have taken. This process is theoretically infinite. In practice, parameters must be established, such as the number of interactions (the number of times that these operations are to be performed), so that the computer can conceivably carry out the tasks and arrive at some result. The series Flora rebellis used datasets (sets of images of plants with anti-Semitic, racist and misogynist names).

Every action to create a latent walk video is, as such, essentially algorithmic. Starting with a vector map of the results for the creation of a model (“Jew”, “blacks”, “women”, etc.), it is possible to load the images based on greater or lesser proximity between the data and the time of displacement between one result (one image created during the machine learning process) and another. In this sense, despite resulting in a video that has a beginning, a middle and an end, its editing is generative and not directed.

Understanding the nuances of the system allowed me to learn from the machines. That is, to move away from an anthropocentric level of me feeling capable of practicing with algorithms, to educating myself for another type of facilitation. I believe I finally understood what Donna Haraway meant with her cyborg manifesto: we must look for ways of breaching the frontiers between nature and culture.

This finding was fundamental for creating the series Flora mutandis, in which I worked with my own criteria to catalog plants, dividing them into groups of species that reference, for example, parts of the body that allude to shoes, that have become, due to their beauty and strangeness, my favorites, among other highly personal classifications.

Any similarity with the famous passage by Michel Foucault—reading a transcription that Jorge Luis Borges had done of a certain Chinese encyclopedia where fantastic beasts were lined up, drawings of dogs and others that looked like flies, so different from us—is no coincidence. This was one of the starting points to develop an artistic methodology designed to understand the scientific genealogy of prejudice and the ways in which it unfolds in language.

The main difficulty has always been how to formulate other aesthetics, alternatives to binarism and the intrinsic standardization of artificial intelligence and the anthropocentric universe that forms the basis of modern science. It is important to say here that Flora rebellis and Flora mutandis use the same format of machine learning (Style GAN2). However, they operate in opposite directions. In the former, I started with categories anchored in scientific racism, striving to simulate the eugenicist method of Galton in his composite portraits, to make the rendering of a generic plant unfeasible. In the latter, I appropriated the title of the seminal work on Brazilian botany, Flora brasiliensis (1840-1906), initiated by Carl Friedrich von Martius (1794-1868), to put into practice everything I learned with Flora rebellis.

In some ways, Flora mutandis summarizes the agenda of Botannica Tirannica: an ecosystem of a wandering science, which moves between supposed reading errors where nameless, rootless hybrid beings flourish. A mutatis mutandis flora that lives “with the necessary changes having been made”.